Heritage Open Day 2020 ‘Hidden Nature’

11 September 2020

By EAFA

Uncovering stories, sites, places and people that traditional history has overlooked or forgotten has always been at the very heart of Heritage Open Days. This year, we are turning our focus onto the natural world. Nature, in its myriad forms, needs cherishing and championing more than ever, and this year EAFA is working with the University of East Anglia’s, Professor Steve Waters, whose AHRC funded project ‘The Song of the Reeds’ investigates how playwriting might complement conservation.

The East Anglian Film Archive (EAFA) showcases four new films combining archive footage with new ‘alternative voice-overs’ written by Professor Steve Waters and recorded by UEA Drama Alumni. The new works are A Necessary Evil,What Peat Remembers,Phytogeography, The Loneliest Woman in England. These narrated archive films explore the region’s unique natural heritage and offer a glimpse at the unseen, ‘hidden’ side of the lives of flora and fauna that call East Anglia’s diverse natural habitats their home. We are very grateful to Professor Waters for his creative reinterpretations and critical reflections on the films and the contexts in which they were produced.

EAFA has also worked in partnership with Norfolk Record Office who have contributed historic documents to the project.

Hidden Nature – from Reclamation to Conservation

A Short Essay by Professor Steve Waters, Professor of Scriptwriting, School of Literature, Drama and Creative Writing, UEA

This crop of astonishing films in the East Anglian Film Archive record rural life from the middle of the last century, as the region succumbed to intensive agriculture as well as the conservation fight-back that provoked. Their flickering frames show butterflies haunting reedbeds from which they have vanished, fens pummelled into ‘productive’ land and bear witness to the ambivalence the English feel towards the nature they hold in trust. Embarking on my own investigation of how playwriting might complement conservation, in my AHRC funded project ‘The Song of the Reeds – Dramatising Conservation’, the films held up an uncanny mirror to my attempt to ventriloquise key figures in conservation over the last century. With the aid of film editor Mellissa Beeken and the skilled performances of the UEA Drama Alumnus company, we’ve re-cut the films, splicing in the monologues as an alternative ‘voice-over’ to the startling images.

'A NECESSARY EVIL' – 1940, Wicken, we hear William Homan Thorpe, an ethologist and conscientious objector make the case to prevent Wicken being drained to feed wartime Britain. (Still: 'Reclamation, 1941)

The tension between conservation and development is clearest in the astonishing Reclamation from 1943, that forms the bedrock of our short film ‘A Necessary Evil’. This thirty-minute silent movie resembles a late work by Eisenstein, a Socialist Realist paean to the impact of labour on land. Its maker and self-styled hero is writer Alan Bloom who, in the tradition of the GPO film-unit, records his struggle to turn Adventurers’ Fen, about fifteen miles East of Cambridge, to farmland, a venture celebrated in his memoir ‘Farm in the Fen’ (1944). It’s a hero-narrative for wartime, a hymn to self-sufficiency in food production as Britain digs for victory. But from this vantage ‘Reclamation’ plays more like a snuff movie of despoliation.

The draining of the fens has been dubbed by Environmental Historian Ian D. Rotherham as ‘England’s greatest Ecological Disaster’ and ‘Reclamation’ is a graphic late account of that process. The evasive intertitles state the fen was the site of peat-workings allowed to revert to, ‘reeds growing on old turf diggings’, as if the film merely tracks land being restored to its rightful state. This would have come as news to local naturalist Eric Ennion who in his lyrical survey ‘Adventurer’s Fen’ (1942) deplores, ‘the sacrifice of those glorious bird-haunted wastes of reed and water for the growing of sugar beet’. Bloom’s triumphal colonial settler narrative disavows any such regret, with the great Reclaimer and his Land Girl proteges hacking through reed and scrub and oak, ‘hinder(ing) the work of food production’.

The pastoral opening is brutally set aside by the scouring of the land, agriculture on the cusp of mechanization as diesel tractors and drag-line ploughs work in step with scythes, spades and horse drawn harrows. The flat-capped men hack at the roots of trees with a kind of vengeful fury, slubbing out lodes chillingly reminiscent of the Trenches they may have endured. This assault reaches a haunting climax with the mining of bog-oaks, fossilised forest remnants, the horizon erupting into showers of peat.

The final shots of a sea of shining wheat must have pleased Bloom’s sponsors, the War Agricultural Executive Committee – but were looked on dimly by his neighbours in the last remnant of undrained land at adjacent Wicken Fen. Acquired by the National Trust in 1899 as a haven of botanical and entomological research, Wicken was – and remains – an oasis of biodiversity in an arable desert. In our re-edit A Necessary Evil, I’ve superimposed the words of ethologist William Homan Thorpe (1902-86), then chair of the Fen’s scientific committee, lamenting Bloom’s deeds whilst attempting to save Wicken from the same fate. Thankfully his arguments prevailed; and in 1948 the Trust re-acquired the very land so ruthlessly ‘reclaimed’ here, allowing it to return to something of the richness celebrated by Ennion.

'WHAT PEAT REMEMBERS' – It's 1923, and we are with Margaret Godwin, wife of Fred Godwin and student of Arthur Tansley as she excavates peat in Wicken and commits to a life of stratigraphy. (Still: 'Breckland Trip, c.1947')

What Peat Remembers in contrast draws on images of a student field expedition, Breckland Trip (1947) alluding to the very history of scientific and conservation work that Thorpe speaks of. Here the soundtrack features the voice of Margaret Godwin (1898-1989), a peat stratigrapher who, with her husband Harry (1901-85), anatomised the fenlands through soil and pollen analysis; much of the couple’s pioneering work took place at Wicken from the 1920s onwards, and I imagine the beginning of that career here.

'PHYTOGEOGRAPHY' - 1911, a gossipy account of the first expedition of the International Phytogeographic Association to Surlingham Broad, through the eyes of Edith Schwarz Clements, American ecologist, dazzled by the pioneering female botanist Marietta Pallis. (Still: 'Broadland Summer, 1965')

The centrality of the Cambridgeshire Fens to the region’s natural history is mirrored in Norfolk by the Broads, a series of shallow lakes and reedbeds which by their very nature have proved more resistant to intensive farming. Phytogeography brings together footage from John Buxton’s film Broadland Summer (1965) made for the RSPB, revealing the competing needs of humans and birds.

Landowner Buxton, like his father, Anthony, was a key figure in the Norfolk and Norwich Naturalist Society, and his management of Horsey Hall estate lured nesting cranes back to Britain in the 1970s after an absence of 400 years. The film, for all its vivid documenting of the mating rituals of marsh harriers or the predations of bitterns, is a rather haughty salvo against human impact on the patchwork of marsh, Broad, meadow and coast which succour the species-rich region. The narrator, bluff actor Frank Duncan, comments sardonically on images of traffic jams in Potter Heigham, inelegant tourists crowding staithes, the result of ‘violent increases in population’ and ‘holiday-makers’ who ‘think of their own pleasures alone’. For all the finger-wagging, there’s a confident post-War sense that all can be saved by ‘planning’ and a patrician tenor of expertise.

Our re-edited version offers an alternative to the masculine monologue that too often defines conservation in the form of botanist Marietta Pallis (1882-1963), Buxton’s neighbour at nearby Hickling Broad, spoken of here by visiting American naturalist Edith Clements (1874-1971). Pallis was a pioneering biogeographer of the Broads, guiding a critical Phytogeographical Expedition in the region in 1911, re-imagined here. With no claim of land or birth or gender privilege her vitalist approach to landscape is rather less sedate than the agreeable High Toryism of ‘Broadland Summer’.

'THE LONELIEST WOMAN IN ENGLAND' - It's 1924, and we join pioneering bird photographer Emma Turner, volunteering as a watcher on Scolt Head island and bedevilled by curious locals. (Still: 'The Norfolk Coast, 1983')

The final film in this miscellany The Loneliest Woman in England is a decoupage of Stiffkey Marsh (1970) made by the former Director of the East Anglian Film Archive, David Cleveland, a lyrical tone poem depicting North Norfolk’s coastal landscape largely secured against human impact if now vulnerable to anthropogenic climate change. In the full film two key regional conservationists feature here: firstly, the central figure of Ted Ellis (1909-1986), probably Norfolk’s best-known naturalist; but also, refreshingly, an avatar of working-class conservation, Warden Joe Jordan, who claims the marsh as his ‘second home’. Jordan’s gentle dialect off-sets the middle-class authority so prevalent in these films. Indeed Cleveland risks discarding a single authoritative voice-over for an polyphony (admittedly all-male. Here on the tideline human action is light in impact, uncovering cockles or crabs at worst; and the film is content to simply gaze at Constable cloudscapes or elemental interfaces between sea and sky reminiscent of the abstract paintings of Agnes Martin.

The dazzling footage of terns evoked another too often forgotten ornithologist Emma Turner (1867-1940) whose tenure as warden on nearby Scolt Head Island in 1926 was characterised by her delight in the diving and nesting of these garrulous birds even whilst she rebuked the deficiencies of their parenting.

Whilst these films may trigger nostalgia at what’s been lost in the intervening years, they remind us that the landscape and natural history of the region has always been in question. And if their sociology speaks of the past, their concern for the non-human is surely central to our present. Ecologist Edward O. Wilson has noted the necessity of ‘biophilia’ as a central human impulse driving us to seek to ‘affiliate with other forms of life’. In the age of the Sixth Extinction, these films offer ample evidence of the wealth of species that comprise ‘Hidden Nature’ in a time when all over the world Alan Bloom’s successors still threaten all our futures.

Steve Waters, September 2020

Recording Nature

Norfolk Record Office

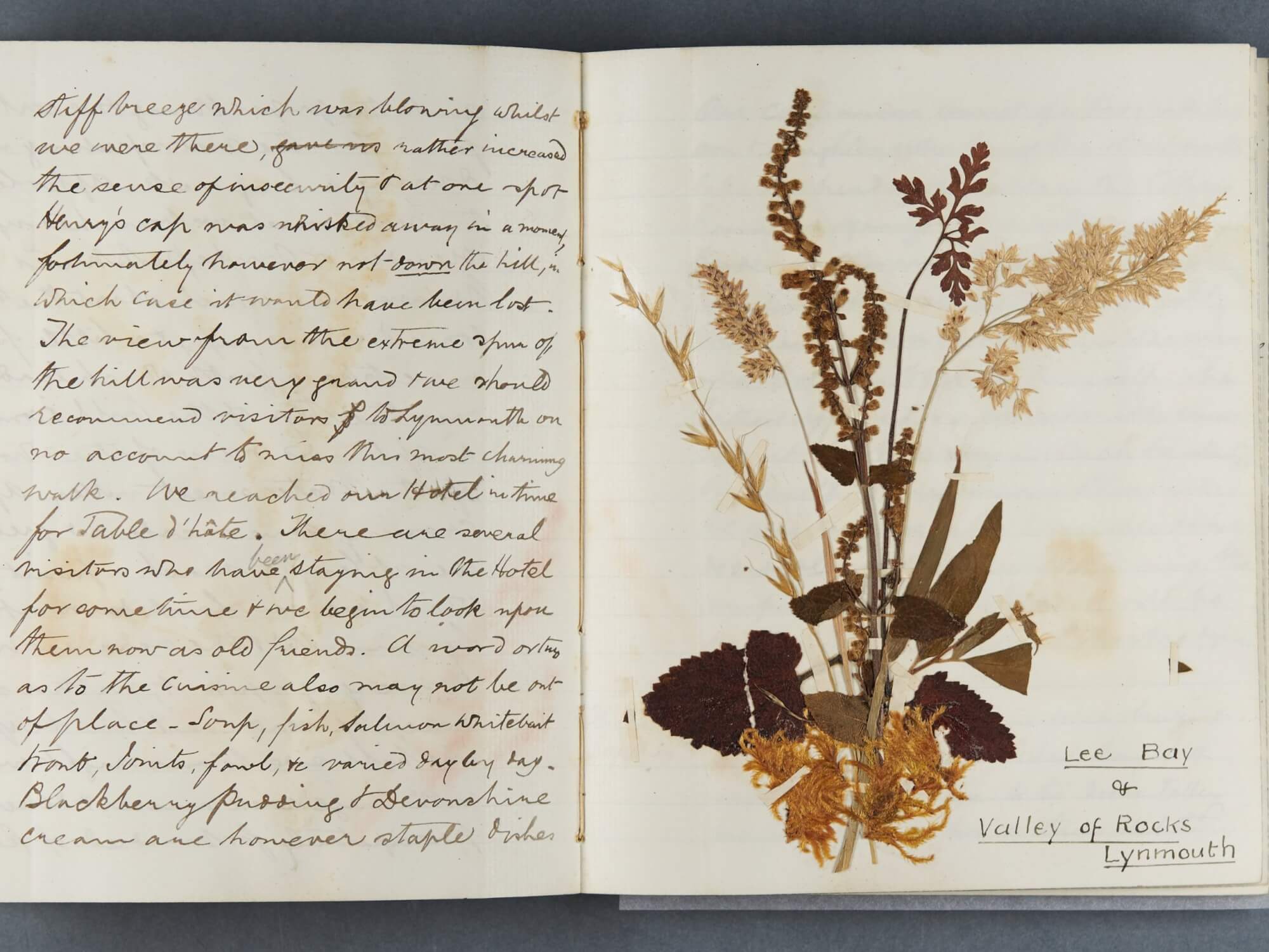

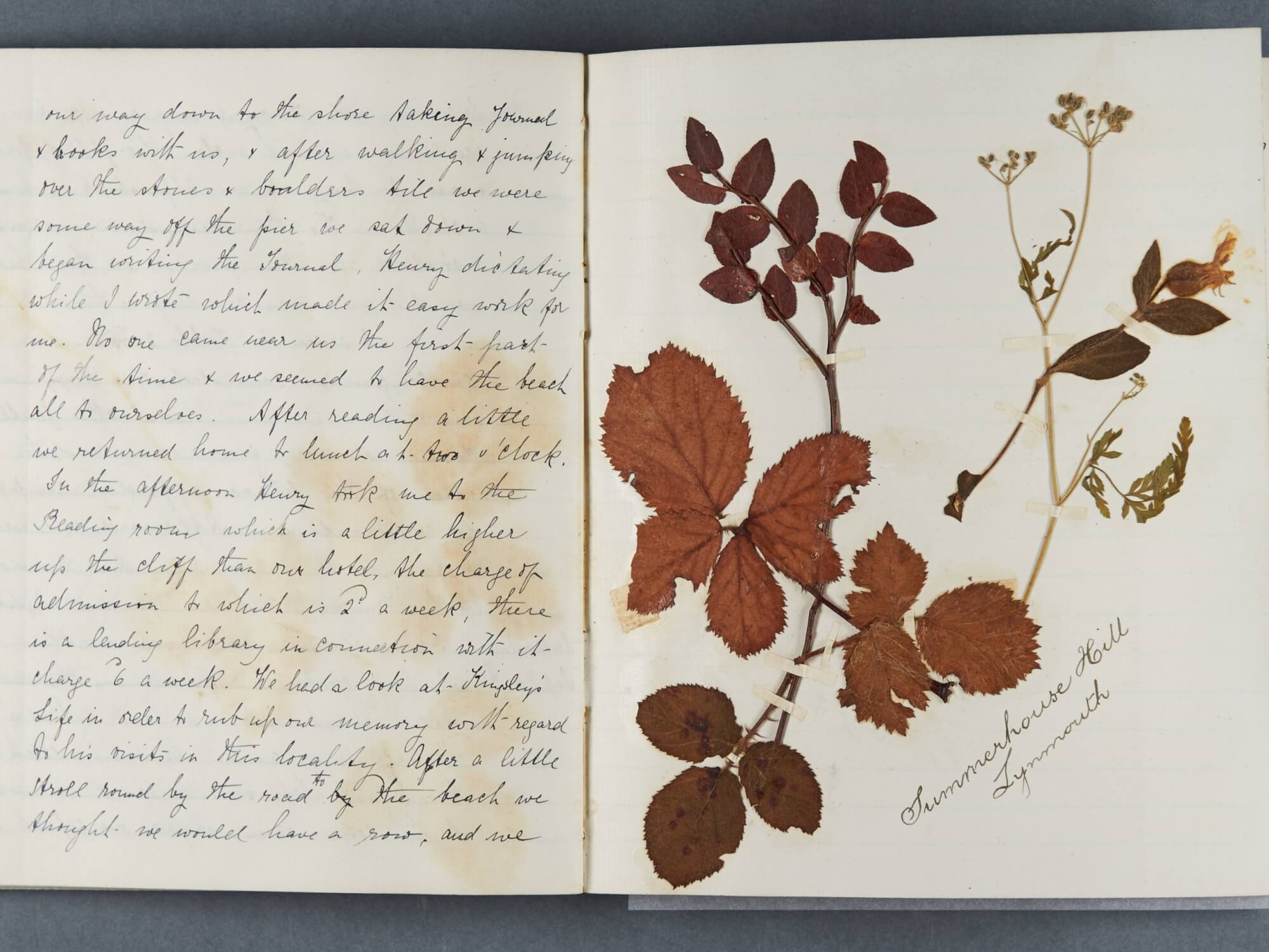

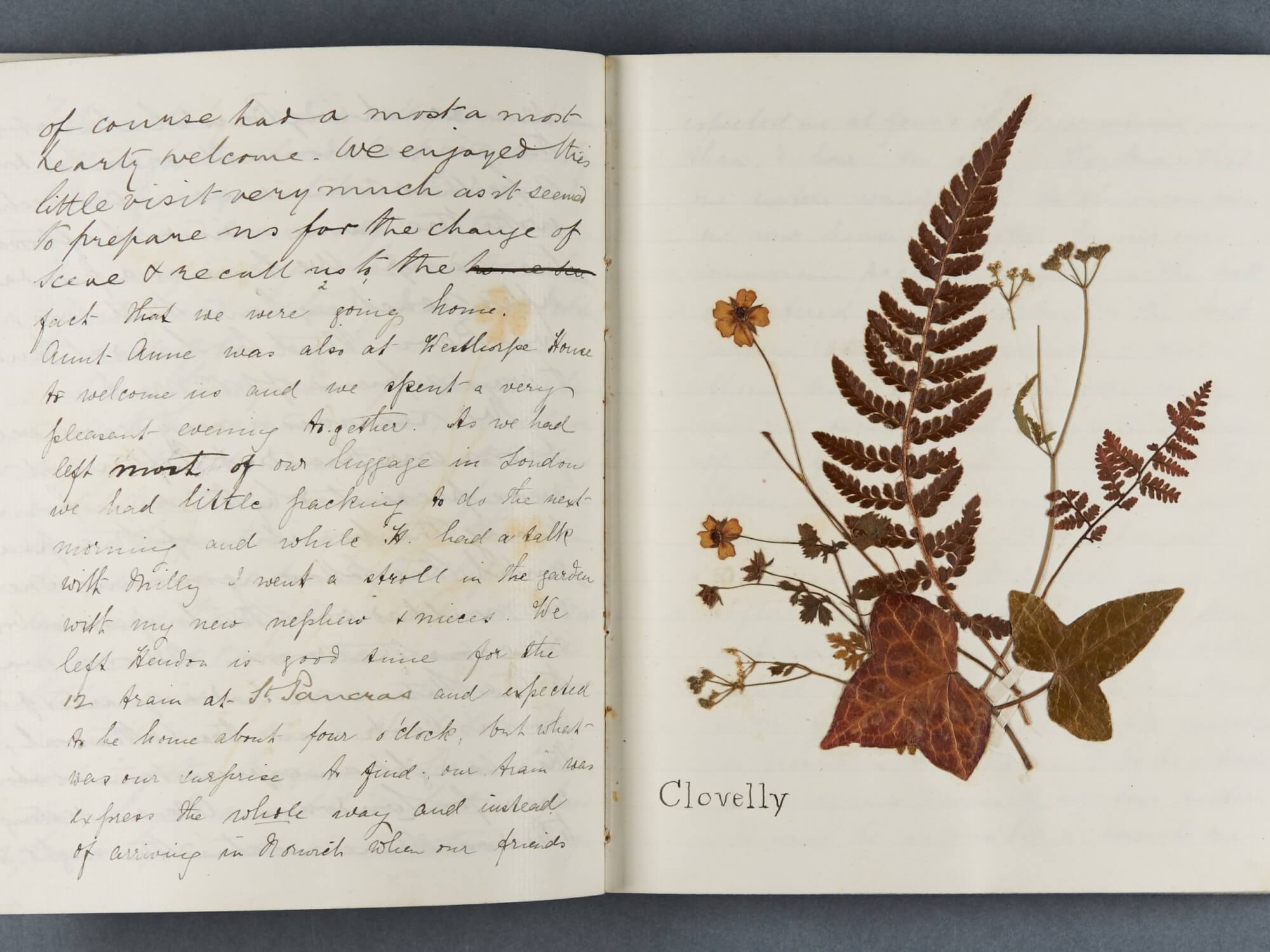

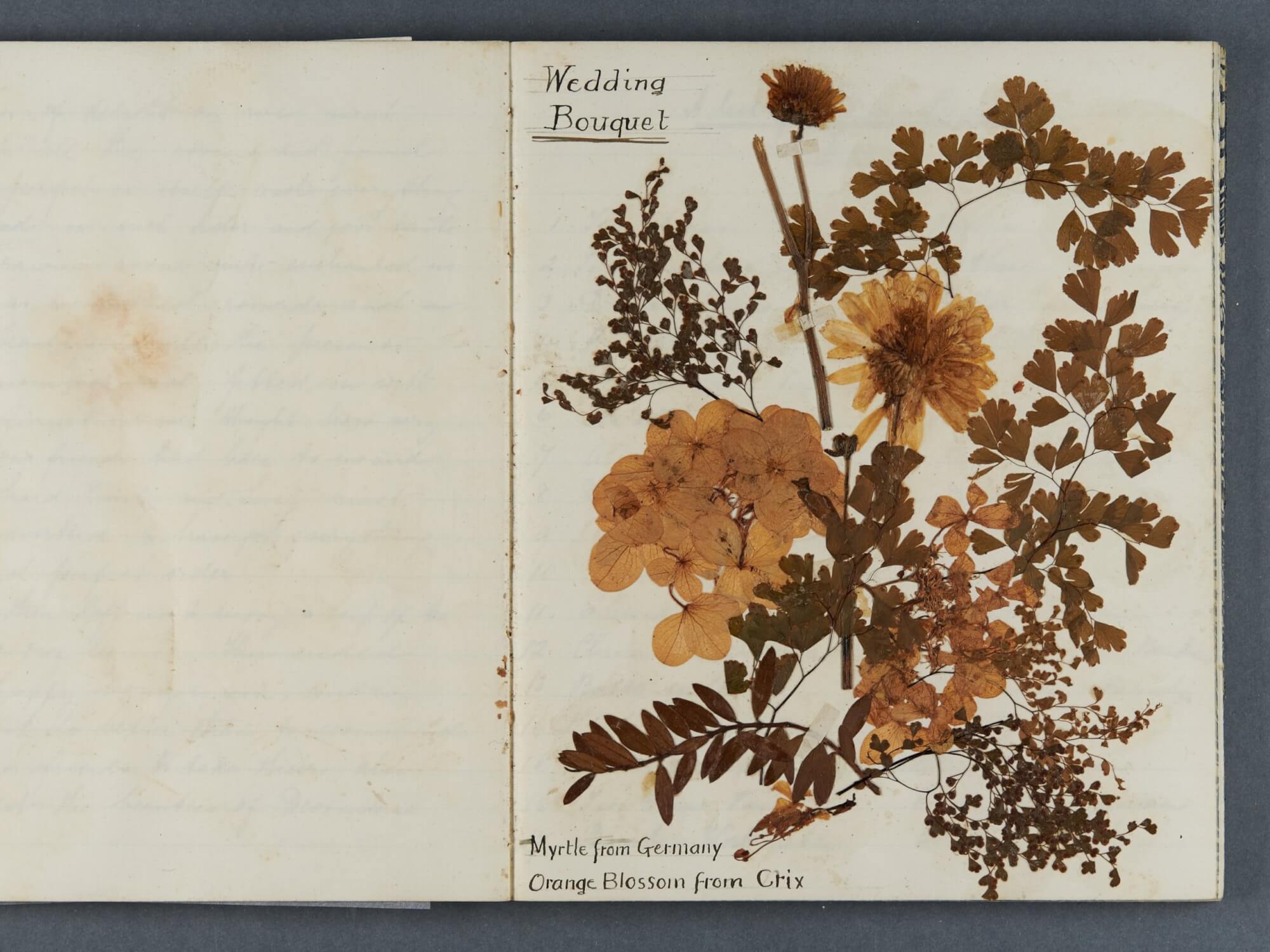

These pressed flowers are included in the diary of Harriet Copeman and her husband Henry John Copeman while on honeymoon in North Devon in 1886. They demonstrate a way of remembering both the flowers from the wedding bouquet but also the scenery the couple saw whilst on their honeymoon.

Lee Bay & Valley of Rocks Lynthmouth

Transcript:

… stiff breeze which was blowing whilst we were there, rather increased the sense of insecurity and at one spot Henry’s cap was whisked away in a moment, fortunately however not down the hill, in which case it would have been lost. The view from the extreme apex of the hill was very grand and we should recommend visitors to Lynmouth on no account to miss this most charming walk. We reached our Hotel in time for Table d’hote. There are several maitres who have been staying in the Hotel for some time and we begin to look upon them now as old friends. A word or two as to the cuisine also may not be out of place – soup, fish, salmon, whitebait, trout, joints, fowl, etc varied day by day. Blackberry pudding & Devonshire cream are however staple dishes …

Summerhouse Hill Lynmouth

Transcript:

…our way down to the shore taking journal and books with us, and after walking and jumping over the stones and boulders still we were some way off the pier we sat down and began writing the journal, Henry dictating while I wrote which made it easy work for me. No one came near us the first part of the time and we seemed to have the beach all to ourselves. After reading a little we returned home to lunch on time – two o’clock. In the afternoon Henry took me to the Reading room which is a little higher up the cliff than our hotel, the charge of admission to which is 2 a week, there is a lending library in connection with it charge 6 a week. We had a look at Kingsleys life in [illegible] up our memory with regard to his visits in this locality. After a little stroll round by the road to the beach we thought we would have a [illegible], and we ….

Clovelly

Transcript:

…. of course had a most hearty welcome. We enjoyed this little visit very much as it seemed to prepare us for the change of scene and recall as to the fact that we were going home. Aunt Anne was alas at [illegible] House to welcome us and we spent a very pleasant evening together. As we had left most of our luggage in London we had little packing to do the next morning and while H had a walk with Milly I went a stroll in the garden with my new nephew and nieces. We left London in good time for the 12 train at St Pancras and expected to be home about four o’clock, but what was our surprise to find the train was express the whole way and instead of arriving in Norwich when our friends…

Wedding Bouquet, Myrtle from Germany, Orange Blossom from Crix