Roger Hewins spoke to Ben Campbell, EAFA’s Graduate Intern, about his practice as an artist filmmaker and the inclusion of one of his films in the Norwich Works exhibition.

We’re mainly here to talk about your contribution to the recent Norwich Works exhibition. But first, your work has previously featured at the Tate Modern, and you had a personal retrospective at Norwich Gallery. Could you give a quick rundown of your career and collaborations with museums and exhibitions?

My personal film practise is in the area of what’s now called artists’ film production, which has been variously called ‘experimental’ or ‘avant-garde’. In 70s and 80s I worked within the workshop movement that had developed at the time. In Birmingham, I was involved in setting up the Birmingham Filmmakers Cooperative. I subsequently moved to Nottingham and worked with the Independent Filmmakers Association. Again, it was a collective workshop, because in the 70s and 80s, whatever description of filmmaker you were, you needed access to equipment. From Nottingham I went to Chicago for a year, where I screened my work at Chicago Filmmakers and in Toronto, and met other artists/filmmakers there. On returning to the UK I moved to Norwich. I became involved in the East Anglian Filmmakers’ (EAF), a workshop that had been going for a number of years.

In Norwich I became aware of the East Anglian Film Archive (EAFA). When archive film programmes were taken around regional venues on 16mm film I was one of the presenter/projectionists, and when I became associated with the university as part-time staff I became further involved in the Film Archive.

What films were you making for the East Anglian Film Archive?

Because of my relationship with Dave Cleveland (then director) at EAFA, I made a number of films for various reasons. Some were for local organisations that came to the Archive because they wanted to include archive clips in films they were making, and I was offered the opportunity to make those films with the client. I recall one for Suffolk & Coasts & Heaths, which was an information film for their visitor centres there.

Others were initiated by the EAFA, in that small pockets of funding came to the Archive for different reasons. For example, funding at the time of the millennium was offered to edit a programme of regional amateur films from the Archive, to represent a century of this genre – the kind of material that rarely got shown in existing contexts. David would often approach businesses and organisations for specific projects. A film of a traditional bakery in North Elmham came about this way, as did the Nestles film included in the Norwich Works exhibition.

There is material that is not completed films but simply recordings or footage of activity and events, sometimes quite random. For example, I filmed material when a Nicaraguan boys’ team came to play for the Canary Cup youth football tournament, which was a way of bringing lads from all over Europe together for two weeks at Yarmouth, and for spotting upcoming talent. The intended programme never found completion, but we shot a lot of footage of them in Norwich and in Nicaragua.

There’s material in the Archive which only happens to be here because David used to occasionally give film to local filmmakers around the region, to record activity as they chose. I had friends in Essex who filmed activities local to them and a member of the Archive staff filmed progressive work on the A47 bypass south of Norwich. The rationale was just to record things that were happening, which might not otherwise have been done.

A still from Cat. 1309 "Nestles Rowntree".

That makes sense. Things like that are not often recorded.

In the mid-90s I shot some film of an oil tanker, the Blackheath, which used to bring fuel to the Sugar Beet Factory at Cantley. This service stopped in the year 2000. When I used to present archive shows at various village halls, a frequent question was “what is an archive film?” I often used to show the Birt Acres 1896 film of trawlers at Great Yarmouth and the Blackheath footage to say “the latter was shot two years ago but no longer happens, so both are clearly archive films despite the separation of a century.” Sometimes, films would be shot for no specific reason other than it was activity happening in their locality, and 20 years later that film can have a life of its own and find its own context in that way. It should also be said that this applies to much of the local history recorded in the Archive, filmed by amateur filmmakers of their everyday lives. Our recorded visual history would be a lot poorer without these records.

I’d guess that’s also true for films of factories and industry, which are not often filmed because they can be dangerous. What makes capturing factories and industry on film interesting to you?

My personal film production is very much concerned with movement, with manipulating or fragmenting movement and with restructuring this to present the familiar in unusual ways. This interest extends to the more documentary work I do, so what is exciting is that things move in factories. They have the most efficient, kinetic machines you can discover. I just find the whole process completely fascinating. It’s the movement and visual energy, really. I think I find those factories most attractive in which lots of little operations contribute to the process – items need to be sorted; wrapped; labelled; counted; packaged etc. Each individual mini-operation has a moving device to achieve this and move the product on to the next.

I’ve filmed in factories in the UK and Europe, on a couple of commercial jobs, so I’ve been to all sorts of factories and filmed products being moved in different ways. It’s just pure visual pleasure. I’ve seen all those things in action, and I try to shoot and edit them in a way that transmits that pleasure. And it also makes a film that’s very kinetic. In a film you might need to jump around between shots in the edit, but the movement actually ties all those actions together.

Walter & Rita Nurnberg, Check weighing and closing cartons, Mackintosh Caley Chapelfield Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1958 ⓒ Norfolk Record Office. With thanks to Norfolk Record Office and Norfolk Museums Service.

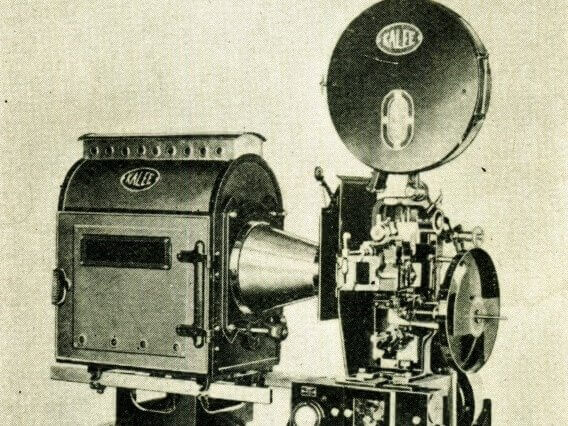

We could compare that with Walter Nurnberg, who was a photographer rather than a filmmaker. He had to capture that kind of movement in singular photographs. What do you think of the way he kind of captured industry?

Well, I think most of his photographs are very kinetic, almost in the sense of anticipation. He likes hands in certain positions as if just about to perform a vital action. There are two or three photographs in which someone’s about to tighten bolts, for example. It’s the anticipation of something that’s about to happen.

It reminds me in many ways about Henri Cartier-Bresson’s “Man Jumping the Puddle” photograph, and the concept of the decisive moment. It’s always worried me a little, that photograph. It shows him in mid-air, hovering just about the water. Is this the decisive moment? But actually, to me, the decisive moment is actually what will happen in the next moment as he lands and starts creating the waves on this puddle. This ‘unseen’ image is as strong to me as the one Cartier-Bresson has captured. It’s the sense of anticipation. Perhaps it’s the sensibility of a filmmaker to think of what will happen next? I think many of the Nurnberg photographs work in the same way.

Also, just thinking about the way he photographs people at work. They’re not portraits. Workers’ lines of sight are always across the frame and often in three-quarter profile so there’s a dynamic and depth created by the eye-lines’ in addition to the focus of the workers to what they’re doing. There is energy in the way people look.

Speaking of Nurnberg, your film “Nestles Rowntree” was included in the exhibition about him. Did you enjoy that experience?

It was good. First of all, it was a brand-new digital scan of the negative, and what came out of the scan was quite mind-blowing, really, because it’s far greater detail than you get on 16mm print. So, there were things happening in there, things in the shadows, that I’d never really seen before.

In the exhibition it had its own little cinema, which added value in a sense, so it looked very presentable. I did hover around a little to eavesdrop when I was in there, and what was clear to me was that people talked about it, whereas they quite often wouldn’t talk about the photographs in quite the same way. That’s partly, I think, because they relate it watching television. Also, it was clear that some people had worked at Nestles, or knew people in their family who worked at Nestles so there was a more immediate relationship than with the photographs. In terms of the context, one function the film did was to link directly to the photographs. The same operations were recorded in both the film and many of the photographs; the manual activity and the workspaces looked the same; as did the equipment. That provides a connection with the people in the photographs and the activities in them over 30-odd years.

A still from Cat. 1309 "Nestles Rowntree".

Yes, and your film did stand out. It was the only film in the exhibition in colour, the only one with audio, and the only one from the 90s, instead of the 50s as is the case for the three other films that were there. It’s interesting to see that it helped immerse people into the exhibition.

It’s at the end of the exhibition as well, so it provides almost a coda to all those photographs. It tells us that activity didn’t stop here in the 50s and shows that the factory continued.

I think the other films in the exhibition were quite interesting in relation to archive film, because what the Archive quite often preserves could be called recordings or documents as opposed to documentary. They’re not articulated films; that’s the difference between mine and the other films. But suddenly, when they’re put into an exhibition together, those documents provide a really interesting context. The “Barnard’s Wire Netting Factory” [Cat. 1635] film directly related to the Nurnberg photographs, whilst “A Car Trip Through Norwich” [Cat. 908] connected the factory and the Nurnberg photographs to the streets of 1950s Norwich.

Curator Dr Nick Warr has said that your film is the only mention in the whole exhibition that the factories closed for good. What do you think you were trying to say in the film with this mention?

The film came about because it was anticipated that the Nestles factory was going to close, so David Cleveland suggested to Nestles that they might fund a short film of operations before they closed. I asked for a couple of days at the factory to talk to a number of people about their experiences of work in the factory and a couple of days to film.

What I didn’t want to happen was for the film to become a catalogue of woes, because there were obviously a lot of people upset because the factory was going to close. However, by the time I went in, the closure was mostly accepted as definitely happening. I think the period of being angry about the closure had passed, and people had moved onto reflecting on their experiences of being there. So, I think I was lucky in that respect. Most people reflected on their experiences of working with their colleagues and things like that and I was very pleased with the contributions used in the film that emphasised the human and social side of working. Very few people mentioned the closure. I didn’t ask people to address the factory closing specifically, I just let them if they wanted to. The secretary addressed it head-on in terms of being ‘gutted’ about it, and the gentleman at the end, who projects the idea of Caley’s re-opening, was upset as well.

The Norwich Works exhibition at Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery. Photo by Ben Campbell.

Finally, what do you think are the general benefits of using film in exhibitions for everyone involved?

Thinking about the shorter pieces in the exhibition, they were a way of showing material that doesn’t normally get shown, and a lot of it was contemporary to the time of the photographs, so it was another way of showing industrial activity within the city and the physical condition of the post-war city around the time. Consequently, these enhanced the experience of looking at the photographs.

I think the Nestles film has a direct connection with earlier photographs of the chocolate factory. It provided a sort of coda to that in terms of the fact that it recognised that this wasn’t just an historical exhibition. The activity continued and changed like everything else. There was a mixture of familiarity and difference. The way people dressed, the hairstyles change but the process remained familiar. It suggests the continuity of that activity. But, of course, in the case of this film, it was actually the closure of the factory that motivated its production, so it also recognises that. It represents a wider arc of the industrial activity that’s taken place in the city.

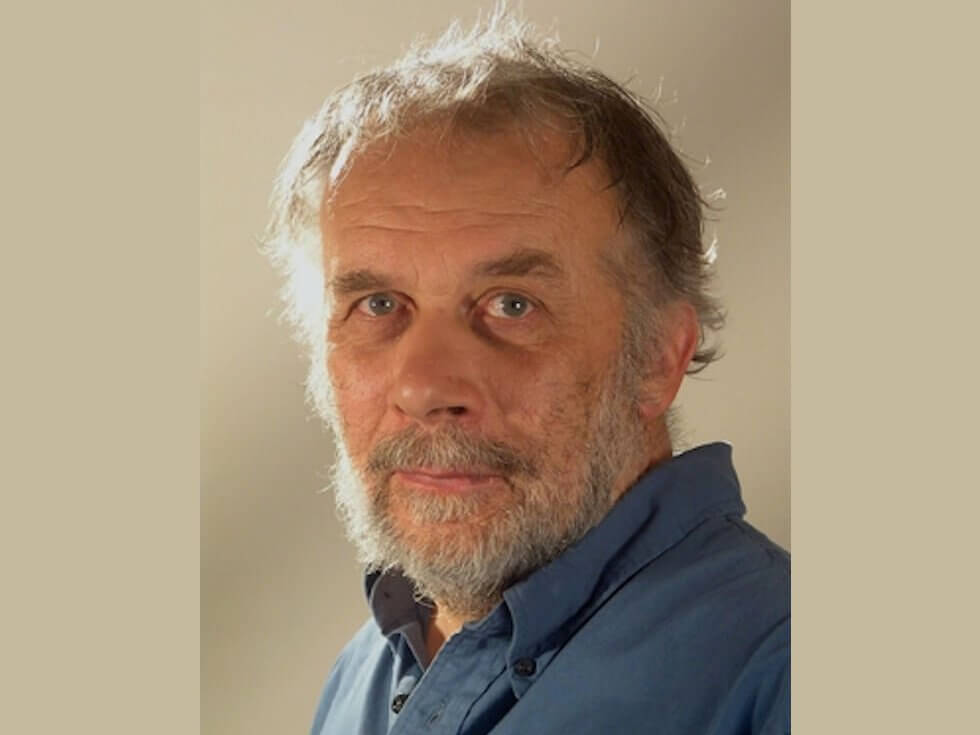

About Roger Hewins

Roger Hewins was born in Birmingham and studied Photography & Film at Trent Polytechnic, Nottingham. He subsequently worked as a filmmaker in Birmingham and Nottingham before moving to Norfolk in 1984.

His film works often break down and then re-present familiar visual events, using techniques such as frame-within-frame imagery or frame re-ordering, to engage with time and motion as fundamentals of cinema.

Hewins’ films are held in collections at the Arts Council and the British Film Institute, and selected works are distributed by LUX. Work was included in the ‘Shoot, Shoot, Shoot: British Avant-Garde Film 1966 – 1975’ exhibition at Tate Modern. He has presented programmes of his work in Chicago, and Toronto. A personal retrospective was exhibited at the Norwich Gallery in 2006, and more recently selected video works exhibited at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts.

Further information: www.rogerhewinsfilms.co.uk

Roger Hewins, courtesy of the artist.

About the project

In 2024, Ben Campbell undertook a graduate internship at the East Anglian Film Archive. Using the Norwich Works exhibition at Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery as a case study, Ben’s research conducted during the internship explores the place of archive film in museum exhibitions.

Find out more about Ben’s research and case study.

Read Ben’s personal reflection on their graduate internship experience.

About Norwich Works

Norwich Works: The Industrial Photography of Walter & Rita Nurnberg ran from October 2023 until April 2024 at Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery. The exhibition was a partnership between Norfolk Museums Service, The University of East Anglia, Norfolk Record Office and The East Anglian Film Archive.

Header image: A still from Cat. 1309 “Nestles Rowntree”.