In the first of a new series of Stories from the Archive, we share an incredible piece of film history.

If you’ve ever visited the Archive Centre in Norwich, you may have noticed the Kalee Cinema Film Projector outside the East Anglian Film Archive offices.

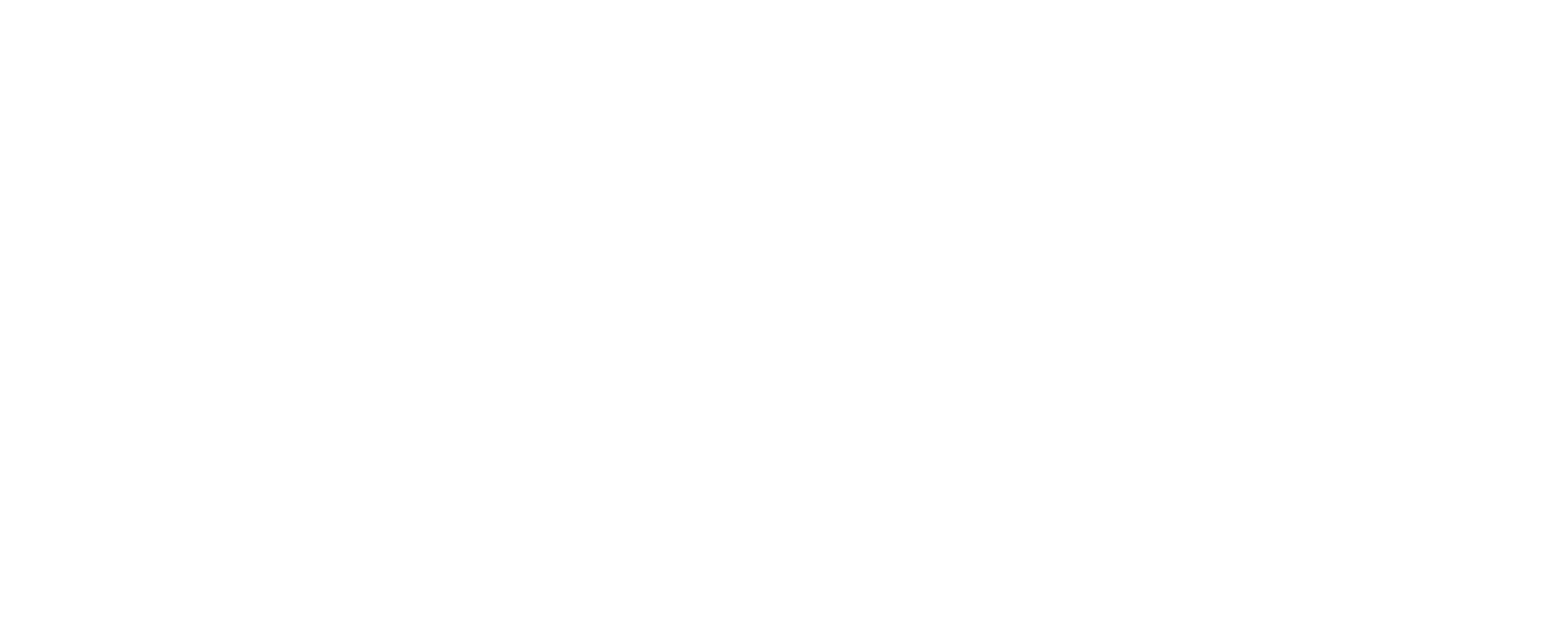

Jane Alvey, Curator, and David Cleveland, founder and former director of EAFA, tell the story of this pioneering technology.

A delicate operation

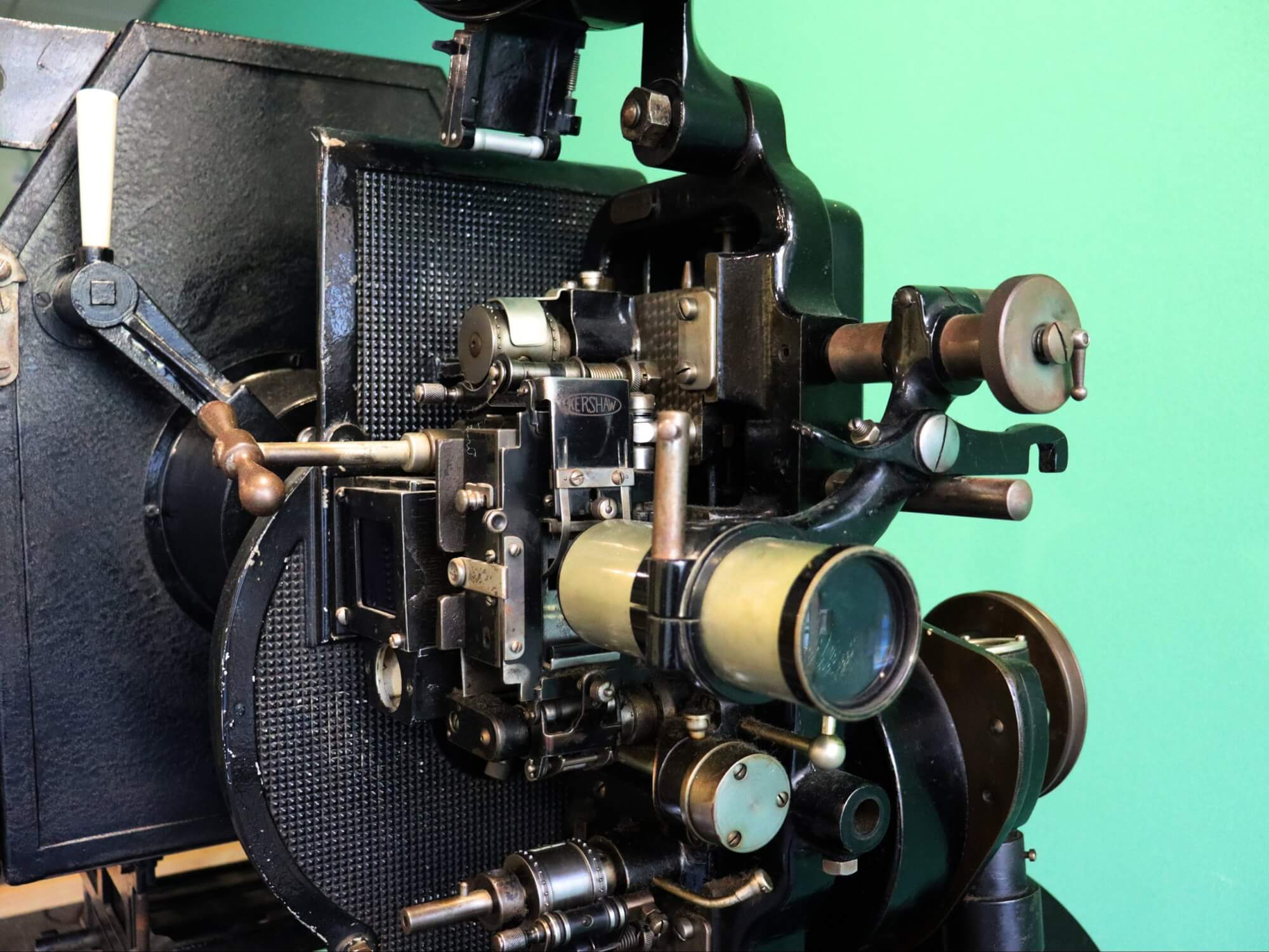

The machine is a Kalee 8 on a Western Electric Universal Base with a disc attachment.

Its parts date from the late 1920s to early 1930s. This cinema projector ran 35mm film, and it was one of a pair enabling the projectionist to make changeovers between reels of the film without interrupting the show.

In the cinema projection box, two projectors stood side by side. A reel of film ran for around 11 minutes. During that time, the projectionist would prepare the second reel on the second projector.

Dots in the top right corner of the picture showed when the reel was ending, and the projectionist would start the second projector. The aim was to create a ‘seamless’ changeover between reels with minimum disturbance to the cinema audience.

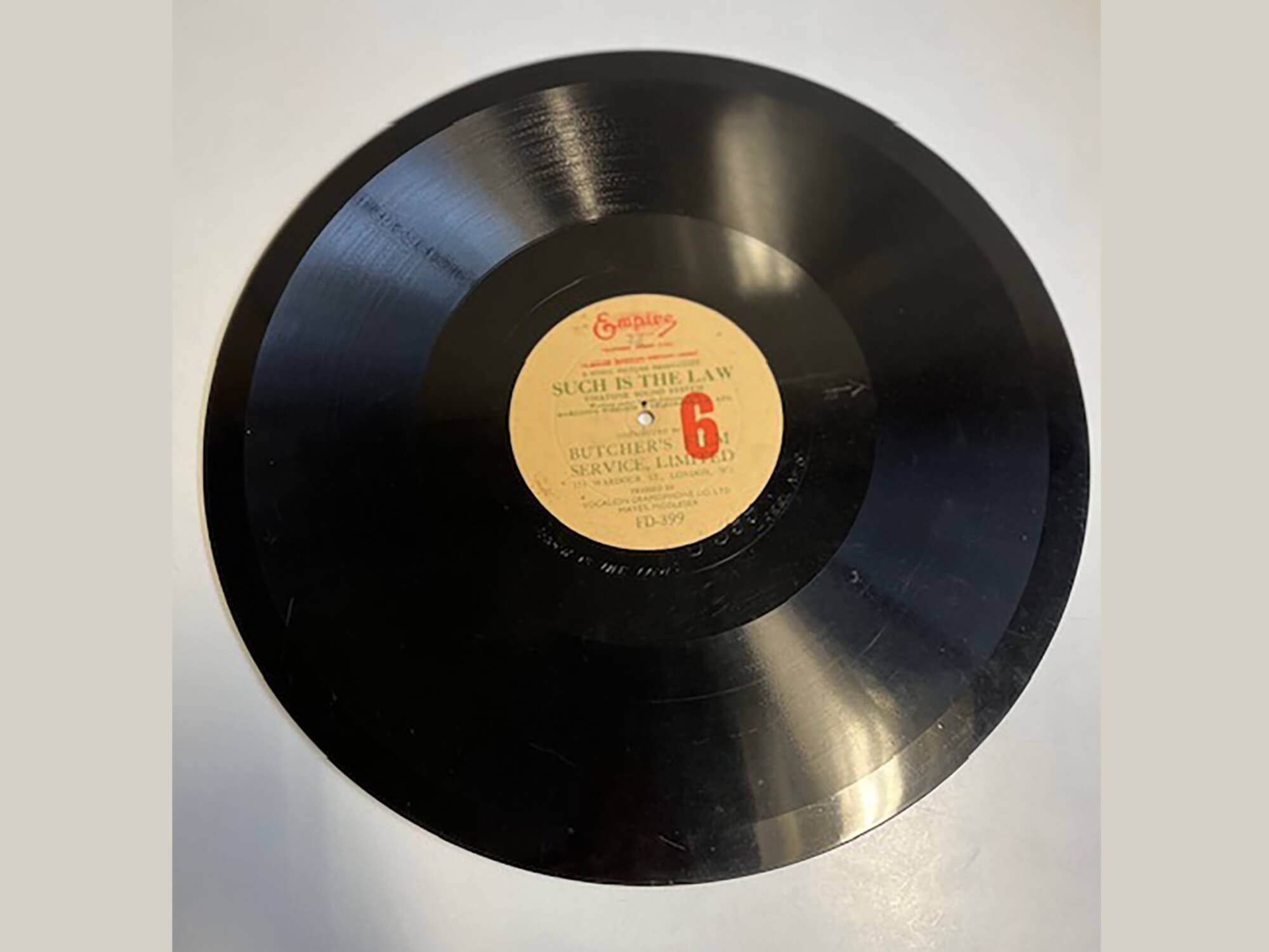

The sound track on the film was designed to stay synchronised with the picture. With one of the sound systems of the time, sound on disc, the projectionist also needed to change the sound track record.

To match the running time of a film reel, a disc ran at 33 1/3 rpm and the needle ran in the groove from the inside of the disc to the outside. What could go wrong!

The Kalee Cinema Film Projector on display at The Archive Centre, Norwich, 2024.

Talking pictures and optical sound

The Kalee projector is a typical example of the type of installation in many cinemas wanting to show the new ‘talking’ pictures, as halls changed over from silent films to the wonder of sound.

This meant investing heavily in buying, or renting, new equipment to show and hear the 35mm films with sound, which were first distributed in the late 1920s.

There were two types of sound systems at this time – one had a sound disc running in synchronisation with the film, the other had a photographic wave form of the sound recorded down the side of the actual film – this was known as ‘optical sound’.

The image size on the film had to be slightly smaller than the old silent picture ratio so as to accommodate the sound track area.

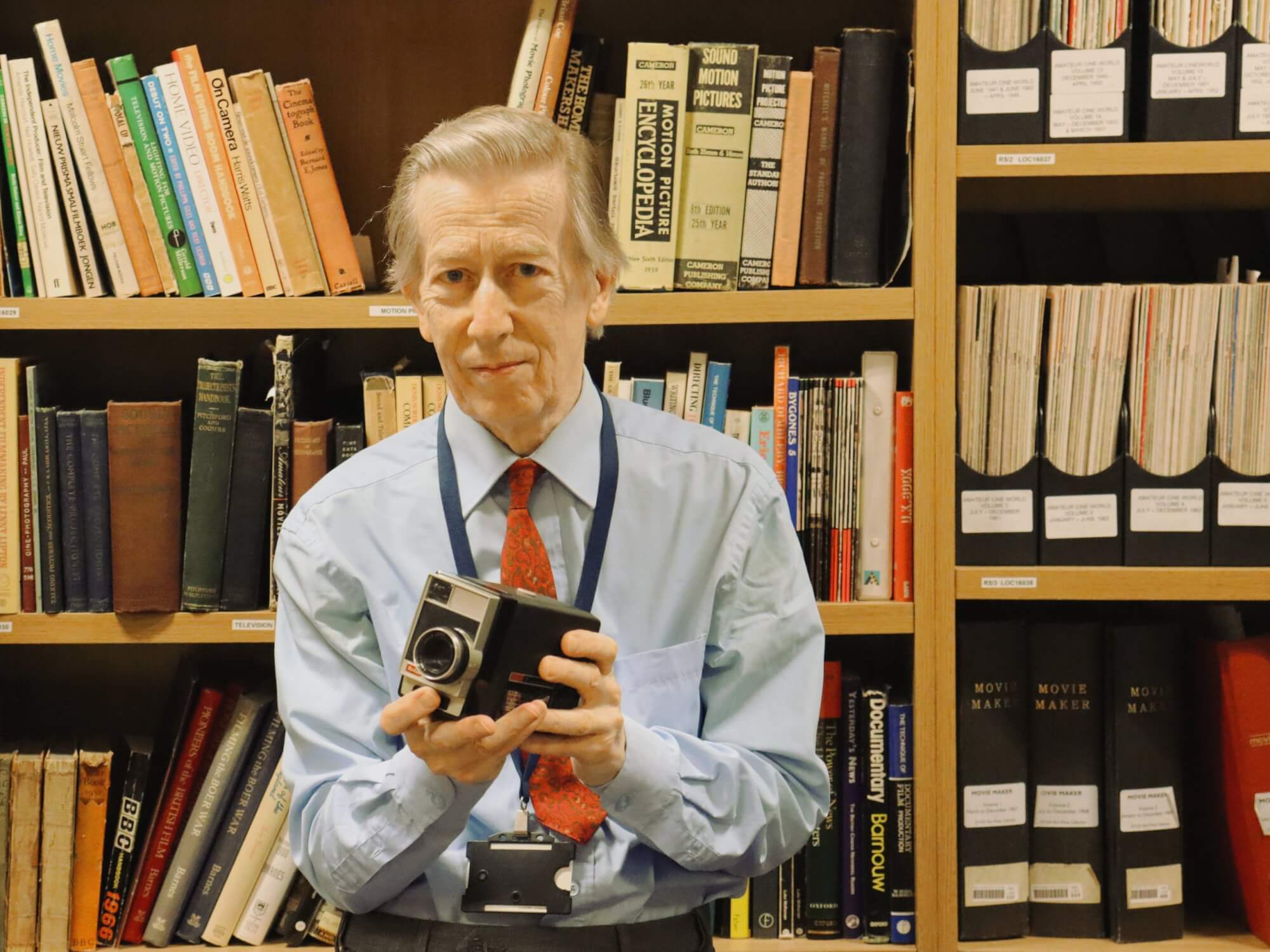

An alternative view of the Kalee Cinema Film Projector as it would have been in its heyday, from Bernard Brown, "Talking Pictures" (The New Era Publishing Co., 2nd edition 1932, page 62). Brown captions the image, "Fig 36, Western Electric Universal Sound Base with Kalee Head and Lamp-House."

For running optical sound films on this machine the film ran from the top spool box through the Kalee projector head (made by Kershaw of Leeds), with light from the burning carbons in the arc lamp projecting the small image on the film through the lens and onto the big cinema screen.

Further down the mechanism is the Western Electric sound head where a small ‘exciter’ lamp shone light through the optical sound track area only onto a sensitive cell, which turned the varying light into electrical signals which were amplified and sent to the loud speakers behind the screen.

The film was then taken up by the revolving spool in the bottom spool container.

With sound-on-disc films a set of records arrived with the film. The film itself retained the silent size image on the 35mm celluloid.

The film had to be laced up in the projector with a start mark in the aperture of the projector corresponding to an arrow on the separate sound disc.

When the electric motor was switched on – driving both the disc turntable and the film projector – the film and the disc started together and hopefully remained in synchronisation throughout the reel.

An example of a sound-on-disc record that would have been played in synchrony with a film.

A new era of film technology

This projector could therefore show both sound-on-film (optical sound) prints and sound-on-disc films.

The ease of making, transporting and showing an optical sound track film outmoded the sound-on-disc system, and by about 1933 no more sound-on-disc films were being released in this country – everything having sound-on-film.

Films arrived at the cinema in cans containing up to 1000 feet of film. Optical sound films ran through the projector at the set speed of 24 frames per second (90 ft per minute) to reproduce good picture quality and unwavering sound. A 1000 ft roll of film lasted on the screen for 11 minutes.

The projectionists were busy, not only showing the reels and watching the arc lamp for maximum brightness as the carbons burnt away, but re-winding each reel of film so it was ready for the next showing, as well as lacing up the next incoming roll of film.

Later, in 1950, films were wound in 2000ft lengths, giving around 20 minutes screen time before a change-over was required to a new reel.

A close-up of the Kalee Cinema Film Projector on display outside the EAFA offices, 2024.

Restoration of the projector

The two projectors were restored in the 1980s by film maker Peter Hollingham, who was a member of the Projected Picture Trust. The trust was established in 1978 ‘to locate, preserve, renovate and exhibit the equipment and data, past and present, of still and moving images’.

This projector was given to the East Anglian Film Archive and its companion went on display at the Museum of the Moving Image.

During restoration, some changes were made to this projector to prepare it as a typical example of an early cinema sound projector. The disc attachment is a rare example, but the pick-up is not the correct type, nor is the turntable.

The motor is original and very few survive. New motors were fitted by Western Electric in the late 1940’s. All Western Electric equipment was leased, never sold.

The motor is variable speed with a locked 24 fps function, and was controlled by the large control box standing next to the machine.

The story continues

The projector remains a prized piece of the EAFA collections, so much so that it is on proud display at The Archive Centre.

Next time you visit The Archive Centre, for research purposes or to attend one of our events, why not take a moment to admire this extraordinary projector, and the period of technological innovation in film that it represents.

Header image: from Bernard Brown, Talking Pictures (The New Era Publishing Co. Ltd, 2nd edition, 1932, page 63). Brown captions the image, “Fig 36a, Western Electric Universal Sound Base with Kalee Head and Lamp-House.”